Course:

Lymington – Frederikshaab – Nanortalik – Julianhaab – Arsuk – Ivigtut – Prins Christian Sund – Lymington

Crew:

Colin Putt – Australia

Iain Dillon – New Zealand

Bob Comlay – UK

Andrew Harwich (Cook) – UK

The Bristol Pilot Cutter Sea Breeze at the Berthon Boat Yard, Lymington, shortly before we sailed at the end of May 1970. The deck had been covered in countless layers of blistered and cracked paint which we’d spent a solid week scraping clean and “holy-stoning” while we fitted her out. Stripping the paint off showed how poor the caulking was in the deck seams, and we used yards of caulking cotton and pitch re-sealing the deck. At the end of the day, the deck fastenings themselves were so rotten that the water just poured in through them. Photographs from the 1971 trip show a new coat of deck paint – expensive to apply and of little effect, the water just found new and more interesting places to run in!

Her topsides were painted in ‘Mischief Yellow’ – a curious colour for a pilot cutter but one which had become something of a tradition since Tilman’s earlier cutter, Mischief, had been repainted yellow in 1961 – the original cream paint being unavailable for purchase in Gothaab. The actual ‘recipe’ for Mischief Yellow varied from refit to refit at the Berthon yard in Lymington, with varying shades from bright yellow through to an almost ‘dayglow’ orange.

The outbound crossing in 1970 gave me my first experience of sailing a Bristol Pilot Cutter – one which was to prove unforgettable in a great many ways. For many of Tilman’s crews, this would have been their first experience of blue water sailing and it’s hardly surprising that some of those crews never quite made the grade. To crew expecting more in the way of sophisticated navigational instrumentation or modern safety equipment, or to those with little experience and no expectations, she probably appeared frighteningly basic. However, to anyone reasonably experienced in traditional working boats, Sea Breeze was a delight; traditionally rigged, with heavy gear but a kindly motion in any kind of sea.

The North Atlantic crossing gave ample time to settle into the watch-keeping routine and to get to know the ship. The rig was simple with the topmast left behind in Lymington, deemed of little use on the North Atlantic crossings and too delicate a spar to have withstood much in the way of weather. ‘All plain sail’ comprised a heavy flax canvas mainsail and jib, together with an equally heavy terylene staysail. An ill fitting but nevertheless effective second hand lightweight genoa for light airs, a tiny flax storm jib which we never used and the flax topsail were the only sail changes available to us, the latter re-purposed as a jury mainsail in mid Atlantic while the gaff was under repair.

The North Atlantic crossing gave ample time to settle into the watch-keeping routine and to get to know the ship. The rig was simple with the topmast left behind in Lymington, deemed of little use on the North Atlantic crossings and too delicate a spar to have withstood much in the way of weather. ‘All plain sail’ comprised a heavy flax canvas mainsail and jib, together with an equally heavy terylene staysail. An ill fitting but nevertheless effective second hand lightweight genoa for light airs, a tiny flax storm jib which we never used and the flax topsail were the only sail changes available to us, the latter re-purposed as a jury mainsail in mid Atlantic while the gaff was under repair.

Tilman’s account of the three week outbound voyage in ’70 was typically brief, the most significant sentence probably being “nothing much of note occurred, except for the night when Bob woke me up to look at a distant luminous object which I had no difficulty in pronouncing to be the rising moon”. In reality, we were closing Cape Farewell for the first time and he’d warned us to look out for ice, suspecting that there would be the odd berg coming down with the east Greenland current. He took the watch after mine and at the turn of the watch I remarked that I’d seen this strange luminous object on the starboard bow. It had long since disappeared (risen behind the low cloud on the horizon?), but he himself suggested it might have been the last rays of the sun catching on a berg. It was midday the following day, having spent an hour studying the chart and tables, that he suggested it ‘might have been the moon’

My first sight of sea ice; the edge of the pack, south west of Cape Farewell, late June 1970. Note the fog rolling off the ice. Even in fog, it’s relatively easy to spot the edge of the pack due to the load noise made by the grinding together of the “growlers” at the edge. As you get further into the ice, the effect of the waves diminishes and the sea becomes calmer. This required all hands on deck, one in the bow or at the masthead looking out for leads and growlers, the rest armed with poles to fend off ice as we encountered it. In general, sailing was infinitely preferable to motoring. The boat was actually far more manoeuvrable under sail than under power, given the offset propeller, and far quieter. With the Kermouth “Hercules” 2 cylinder diesel running, life below deck was distinctly unpleasant !

After rounding Cape Farewell and making the latitude of Julianhaab, we headed back east in toward the coast, hoping to make an easy landfall and set the climbers ashore. However, we hadn’t bargained on finding what turned out to be the worst ice conditions on the coast for several years.

Somewhere in the region of Julianehaab in South West Greenland. At the time we were around 40-50 miles from the coast, and were searching for the ‘shore lead’ which during summer runs parallel with, and close to, the coastline. It provides an ice free channel – protected from the open see by the pack ice outside – through which local ferry traffic and fishing boats are supposed – according to the Arctic Pilot – to be able to make easy passage.

Shipping trying to get into the various small ports and fjords need to find a route through the pack ice, then follow the shore lead north or south to their destination. Easier said than done!

What looks relatively open pack here actually is a little more tricky. The tongues which protrude from the floes beneath the water, together with the fact that the ice itself is constantly moving, makes keeping a sharp lookout from aloft essential. An hour or so with feet jammed into the shrouds at the masthead, shouting directions to the man on the helm, was tiring work.

When sailing in relatively open water, we had a few close encounters with small pieces of floating ice, sometimes tricky to spot if there was much in the way of surface waves. A small piece the size of a small car could do significant damage if struck, but floating mostly below the surface could be very difficult to spot. A sharp lookout was needed from a man in the bow, armed with a long ice pole, was invaluable here since the view ahead from the cockpit was limited when under sail. At mealtimes and during the short murky night, we moored to floes using a simple, well rehearsed manoeuvre. Running under motor, we would drop a man from the bowsprit, and land him on a suitable floe with an ice axe. He would then select a suitable natural outcrop of ice, using the axe to help sculpt a bollard. We would then pass him a warp which he’d make fast so we could pull ourselves back in and bring him back aboard. These ice bollards were easily strong enough to hold the weight of the vessel.

Robin Knox-Johnston gives an account of a Greenland voyage where he used anchor and chain on a floe. To test the strength of the ‘mooring’ he motored back from the edge, pulling the chain taut, and his comments about ‘fly fishing with an anchor and chain’ tell the rest of the story!

The photograph above was taken from the ‘summit’ of a floe against which we lay for a week, the ice having closed in around us. We had managed to manoeuvre the boat into a position where two reasonably large floes touched beneath the keel, providing in effect a floating dock in which we lay reasonably snug for the week. Initial misgivings, and the occasional strange creak from the hull, caused us to start making evacuation plans, but in the end, when the fog lifted, the land became visible and the sky turned blue, we relaxed a little. The main fear actually became the fear that we’d be spotted by one of the many small planes which occasionally flew over the ice, recording the unusual ice conditions. The prospect of being the unwitting objects of an unnecessary and unwelcome ‘rescue’ mission was one which appealed to none of us.

The photograph above was taken from the ‘summit’ of a floe against which we lay for a week, the ice having closed in around us. We had managed to manoeuvre the boat into a position where two reasonably large floes touched beneath the keel, providing in effect a floating dock in which we lay reasonably snug for the week. Initial misgivings, and the occasional strange creak from the hull, caused us to start making evacuation plans, but in the end, when the fog lifted, the land became visible and the sky turned blue, we relaxed a little. The main fear actually became the fear that we’d be spotted by one of the many small planes which occasionally flew over the ice, recording the unusual ice conditions. The prospect of being the unwitting objects of an unnecessary and unwelcome ‘rescue’ mission was one which appealed to none of us.

The experience of being ‘beset’ in pack ice was something new for us all, including the Skipper. He’d had many scrapes with Mischief, particularly outside Angmassilik on the East Coast, but this was the first time that he’d experienced a week drifting with the pack ice.

On the voyage south from Faringehaven, we stood out to the west, well clear of the pack ice in Davis Straight before heading south. This gave us a few days of sailing, uninterrupted by ice, which after several days of motoring in ice was a distinct pleasure. The only problem was that we all underestimated the distance traveled per watch, her speed under sail being significantly faster than under motor, and by time we realised the distance we’d run, we had overshot the latitude of Arsuk Fjord by a considerable margin. We made our way back to the north before heading east into the coast again. This time there was little in the way of pack ice, and when the coast appeared through the evening mist, we were hard pressed the locate the landfall on the chart. There was a prominent radar installation on the nearest headland which was nowhere to be found on the chart or in the pilot. While Tilman’s charts and copies of the Arctic Pilot were typically out of date, another probable explanation was that the station was part of the US DEW line (Distant Early Warning) establishments, which never appeared on the charts anyway.

We moored to a floe for the hours of dusk, and in the morning sailed slowly into the fjord to find the settlement of Arsuk close to the entrance. Bypassing Arsuk, we headed inland to the mining settlement of Ivigtut. The product from the mine here was cryolite, a rare material used in the smelting of aluminium. This operation had been the largest cryolite mine in the world, the only other commercial operation being in South Africa. However, by 1970, the mine at Ivigtut was all but worked out and the main work going on during that summer was the reclamation of ore from previous spoil heaps and from an old jetty, built early from lower grade ore but now deemed worth retrieving.

When we arrived, a couple of Danes arrived by Land Rover from the mining settlement less than a mile away, bearing invitations to showers and food. HWT declined the invitation, preferring to catch up on his sleep, but the rest of us accepted eagerly. Often on watch, we’d laugh and joke about those dream meals that we would have when we got back home, but by time we left the showers in Ivigtut, which alone would have justified the short walk, we found a feast laid on for us which surpassed most if not all of these visions. The meal, washed down with copious quantities of Danish lager, was followed by a delightfully sophisticated evening listening to the mining crew’s expensive hi-fi installations and drinking Carlsberg Elephant beer and Johnny Walker Black Label. The mine was mainly staffed by Danish graduates, enjoying tough contracts and weather conditions tempted by good tax breaks and high salaries. As we learned much later, and further down the coast, that the Ivigtut hospitality was something of a legend. We declined their invitation for a lift back to the boat in the small hours, and staggered back under our own steam.

The anchorage in Tasermiut, a beautiful valley off Prins Cristian Sund in Southern Greenland, provided a tranquil setting for a few days climbing for Colin and Iain, and a few days painting, deck caulking and other minor repairs for Andrew, the Skipper and myself. One afternoon, I took went for a quiet scramble up the side of the valley above the anchorage, and spent a happy hour or so just soaking in the cool sun and marvelling at the tranquility of the place. There were the remains of a Viking encampment down towards the shore of the fjord, and a beautiful variety of alpine flowers. Only the incongruous vapour trails from the transatlantic flights, which pass over Cape Farewell on a great circle route from Heathrow to New York, gave any hint that the so called civilised world was still out there. Of all the places I’ve been in the world since, few come close in terms of natural, unspoilt beauty.

This view to the south down the valley showing Sea Breeze riding at anchor at the bottom of the frame, three small bergs aground close by. In the distance, Prins Cristian Sund runs East/West.

We spent the last week of the cruise at this anchorage while Colin and Iain took off into the mountains in search of something to justify the climbing objective while the Skipper and I worked our way around the obvious, visible damage sites applying tingles, re-caulking deck seams and checking sails and rigging. Andrew spent the time sorting out the remaining foodstuffs, checking the water supplies, the paraffin and meths for cooking and planning for the voyage home.

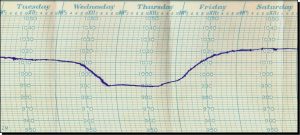

That trip back across the Atlantic in 1970 is given rather more prominence than usual in ‘In Mischief’s Wake’, even adopting a serious tone. In fact, she had a serious leak down below the waterline on the garboard strake, and numerous other smaller leaks – the result of a couple of months of fun and games in the ice. I well remember the first couple of nights out from the coast, one of which had the crew fully occupied just keeping the boat secure in storm force winds. Hove to with just about 6 feet of luff left on the mainsail and the gaff clearly broken. During one watch on deck I’d lashed myself into the cockpit since there were serious seas breaking over the deck from time to time. Looking down into the companionway I could see Iain and the skipper taking turns at the bilge pump without a break while Andrew and Colin shifted stores and attempted to locate the leaks. We could do nothing about the gaff till the wind took off, and with Colin and Iain both running on two cylinders due to seasickness – we’d been two months away from real seas – things were pretty bloody desperate! I think I’d got beyond the stage of being scared, but still that steady smile round the Skipper’s unlit pipe seemed to restore order.

For more notes on life aboard one of Tilman’s pilot cutters, take the menu option for ‘Life aboard‘ or simply click the link.