A few notes on life aboard Tilman’s Pilot Cutters

This page contains notes on life aboard the Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter “Sea Breeze”, based on my experiences of the 1970 and 1971 Greenland voyages with Bill Tilman. If you’re here because you know of the subjects, then I need explain no more. However, if you’re just here out of idle curiosity, or perhaps a love of old traditional working boats, then read on. Comments and suggestions welcomed.

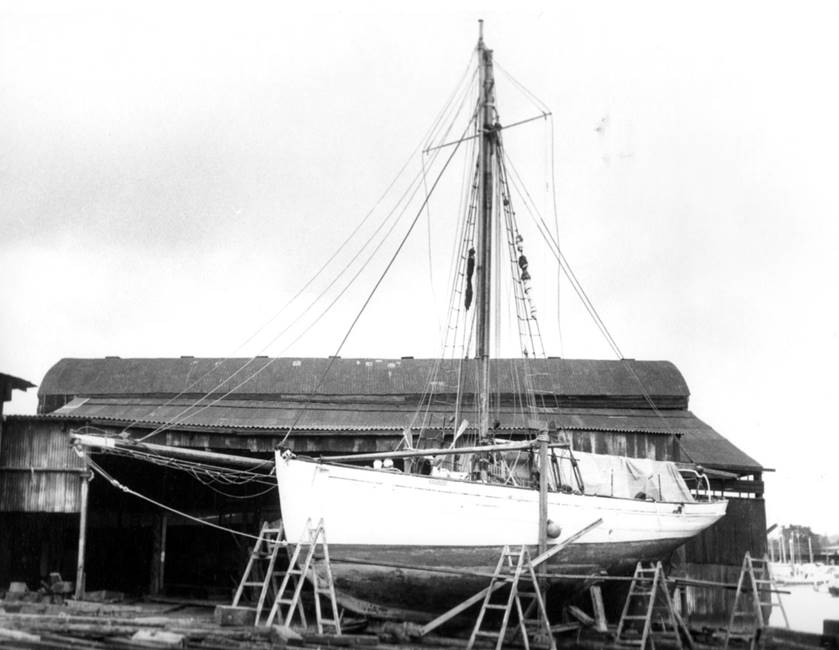

The Bristol Pilot Cutters worked in the Western Approaches to the English Channel at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Competition to pick up vessels was fierce, and as a result these cutters developed a reputation as sound, fast sea boats in all weathers. During their working lives, these boats were sailed by one man and a boy – the pilot owner playing no role in the day to day running of the vessel. Tilman owned three of these vessels during his sailing years, “Mischief”, “Sea Breeze” and “Baroque”. “Sea Breeze”, being the most traditionally rigged and largely unaltered, provided a good insight into the workload of their original crews.

Bill Tilman pushed his pilot cutters well beyond their intended environment, his first voyage taking him south to Patagonia and a crossing of the ice cap. Mischief made several more southern ocean voyages and numerous excursions through pack ice into both the coast of Greenland and points north before being finally abandoned, sinking off the island of Jan Mayen following a disastrous encounter with ice in 1968 . After the loss of Mischief, Tilman understandably felt that any other cutter would always be second class in comparison, as a result, his initial views on Sea Breeze were far from complimentary. The 1969 voyage was clearly an unmitigated disaster given that she had lain little used, in inshore waters, for years previously. To make an Atlantic crossing and expect to accomplish anything of note was typically over ambitious.

The 1970 trip, however, was a different matter. Some of the faults had been rectified, and with a good crew, the voyage was classed as one of his most enjoyable. By the time we returned to Lymington, he was already comparing her with Mischief in a far more favourable light – admitting that she did, in fact, have a number of advantages.

Tilman’s satisfaction with Sea Breeze was complete by the 1971 trip, a voyage marred only by his dogged determination to attempt an ice-free entrance to Scoresby Sound. By the time Sea Breeze was lost the following year, he felt as close to this boat as he had to her predecessor. She was the oldest of the three, having been built by Jackie Bowden of Porthleven in 1899, and also the most traditional in rig and fittings.

Under Sail

An old pilot cutter sails well, easily and safely in a reasonable wind in open water but inshore needs much room to manoeuvre. Sea Breeze was at her best, and most satisfying, on a broad reach, with a reasonable sea running. In these conditions, you could lash the tiller and make only minor corrections to the helm throughout a two hour watch, leaving her to sail herself. At other points of the wind she was harder work. While it provided a couple of hours of amusement trying to get her to point close to the wind, the amount of leeway she made rendered this a fairly pointless – and in inshore waters dangerous – activity. Running before the wind required total concentration, with a boom that weighed close to a ton with its reefing gear and a gaff that from the cockpit looked like a toothpick. Tilman himself makes much of losing spars, but the fact that the gaff on Sea Breeze was brought down on three out of her four trips speaks more of design than lack of seamanship. The weight of the mainsail, coupled with rolling brought about by running down heavy Atlantic seas late in the summer, caused the gaff enormous stress with an inevitable end result.

An old pilot cutter sails well, easily and safely in a reasonable wind in open water but inshore needs much room to manoeuvre. Sea Breeze was at her best, and most satisfying, on a broad reach, with a reasonable sea running. In these conditions, you could lash the tiller and make only minor corrections to the helm throughout a two hour watch, leaving her to sail herself. At other points of the wind she was harder work. While it provided a couple of hours of amusement trying to get her to point close to the wind, the amount of leeway she made rendered this a fairly pointless – and in inshore waters dangerous – activity. Running before the wind required total concentration, with a boom that weighed close to a ton with its reefing gear and a gaff that from the cockpit looked like a toothpick. Tilman himself makes much of losing spars, but the fact that the gaff on Sea Breeze was brought down on three out of her four trips speaks more of design than lack of seamanship. The weight of the mainsail, coupled with rolling brought about by running down heavy Atlantic seas late in the summer, caused the gaff enormous stress with an inevitable end result.

Watch keeping

Once at sea, we set two hour watches with a single crew member having full responsibility on deck for the duration of the watch. With a sailing crew of four and a full time cook, this worked well, enabling a good mix of work and rest and ensuring that we were fit for anything the weather threw at us. By way of illustration, the watch rota from the 1970 trip looked like:

| 00:00 – 02:00 | Bob |

| 02:00 – 04:00 | Skipper |

| 04:00 – 06:00 | Ian |

| 06:00 – 08:00 | Colin |

| 08:00 – 10:00 | Bob |

| 10:00 – 12:00 | Skipper |

| 12:00 – 14:00 | Ian |

| 14:00 – 16:00 | Andrew (Cook’s watch) |

| 16:00 – 18:00 | Colin |

| 18:00 – 20:00 | Bob |

| 20:00 – 22:00 | Skipper |

| 22:00 – 24:00 | Ian |

With the cook taking the afternoon watch each day, the rest of the crew watches moved forward by two hours. In heavy ice, or in inshore waters where the manoeuvrability of the boat required two pairs of hands, we doubled up on watches. Otherwise, she was sailed single-handed on watch, extra hands only being called for sail changes which, given the size of the gaff main and the weight of the traditional flax canvas, must have taxed to the limit the abilities of the original ‘man and a boy’ crew.

When in the ice, all hands would normally be on deck. One at the masthead spotting clear leads, the others attempting to fend the boat off small pieces of ice. At night, which was more of an extended dusk during the high summer, we would hand the sails and moor to a convenient ice floe until morning – enabling most of the crew to get some sleep before the next days sailing.

Since we normally only worked six hours of the day, there was plenty of time during the outbound Atlantic crossings to relax and read. Between us, we had a large library of fiction, enough to keep us all distracted for the duration. In fair weather, the crew would scatter themselves around the deck, a favourite reading spot being the dinghy along with a comfortable assortment of sails and ropes. Usually the man on watch would have a companion in the cockpit, discussing a variety of topics as wide and varied as the content of the ‘library’. In foul weather or heavy seas, the off duty crew would retreat to their bunks and read, mealtimes then becoming the social high points of the day.

The return crossings tended to have less time for leisure pursuits, being mostly taken up with general repairs to leaks opened up during a summer in the ice. Also, with the onset of August, the North Atlantic gales tended to keep us occupied with repairs to both canvas and spars.

The subject of food

The role of the cook on these voyages was one which I never envied. As well as planning and preparing meals for five from a limited portfolio of ingredients, he had to manage the reserves of fresh water and also – in all weather – took the afternoon watch each day which enabled the gradual rotation of watches over time.

To emphasize the problem facing the cook, the following list shows the basis of the ships stores for a four month voyage. Tilman’s attitude towards expedition fare has been written about at length by far more auspicious writers than this, but much of the apparent frugality of our diet could be put down to the need to sensibly use the limited stowage space available. At the start of the voyage, all of the stores had to packed under seats, floors and bunks – tins with their labels removed and identifying marks painted on them, vegetables and bread in a locker in an open area near the fore peak. Locating and retrieving the ingredients for a meal required forward planning by the cook – especially if a key ingredient was located under the bunk of a crew member recently off watch!

Heading up the stores manifest, eight dozen tins of corned beef, from which the cook could fashion a variety of stews, pasta sauces and curries. Four dozen tins of pilchards and four dozen tins of sardines, along with half a dozen 10lb farmhouse cheddar cheeses gave a variety of options for lunch. Dried eggs provided a breakfast alternative, while dried vegetables in the form of carrot and cabbage, often made up with part sea water to preserve the fresh water stock, gave us our ‘five a day’. During the 1971 voyage, an encounter with a Norwegian whaling ship north of Iceland provided some welcome relief from the bully beef.

On the outbound Atlantic passage, the tins and dry supplies were supplemented by a stock of hard white cabbages, potatoes and onions, all of which lasted well when stored in a dark and preferably dry place. We also sailed with a store of ‘double baked’ bread, white loaves cut into 1 inch slices and double baked for longevity. Such bread would normally last for three to four weeks. In Greenland, we usually managed to stock up with black rye bread, which had a remarkable lifetime, taking a month or so before it started to turn green around the edges. In addition, the boats carried a supply of Lifeboat Biscuits in tins, which the cook would ration out with a lunch of cheese, sardines or pilchards once the on board bread had either been consumed or had gone too mouldy to contemplate.

On the outbound Atlantic passage, the tins and dry supplies were supplemented by a stock of hard white cabbages, potatoes and onions, all of which lasted well when stored in a dark and preferably dry place. We also sailed with a store of ‘double baked’ bread, white loaves cut into 1 inch slices and double baked for longevity. Such bread would normally last for three to four weeks. In Greenland, we usually managed to stock up with black rye bread, which had a remarkable lifetime, taking a month or so before it started to turn green around the edges. In addition, the boats carried a supply of Lifeboat Biscuits in tins, which the cook would ration out with a lunch of cheese, sardines or pilchards once the on board bread had either been consumed or had gone too mouldy to contemplate.

Tabasco sauce was a Tilman essential. Anything could be made edible with the inclusion of a few drops and he laced most meals heavily with it – hardly complimentary to the cook! As part of the deal for Sea Breeze, he had also inherited a seemingly endless supply of tins of “Sir Athol Oakley’s Stew”. These kept appearing in the corners of various lockers during the 1970 trip, and frankly needed the Tabasco to render them edible.

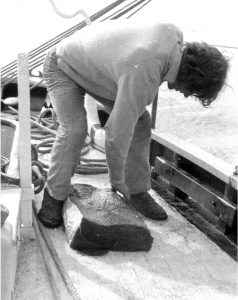

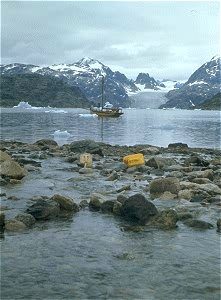

The limited fresh water supplies on board also required close and constant management by the cook. On both trips we ran low on fresh water, despite cooking and washing with sea water. Both times, as the pictures here illustrate, we had to resort to unusual means for replenishment. In 1970, having been kept off shore by an unusually heavy belt of pack ice, we used rainwater and melt water from the pack itself to replenish the tanks. A long drawn out job but arguably easier than in 1971 where we had to row backwards and forwards with plastic jerrycans of water drawn from a nearby stream. In the left hand picture, you can just make out the ice axe and the saucepan used to scoop up the melt water and in the right hand shot, a rudimentary dam is just visible, complete with plastic piping and plastic cans slowly filling.

The limited fresh water supplies on board also required close and constant management by the cook. On both trips we ran low on fresh water, despite cooking and washing with sea water. Both times, as the pictures here illustrate, we had to resort to unusual means for replenishment. In 1970, having been kept off shore by an unusually heavy belt of pack ice, we used rainwater and melt water from the pack itself to replenish the tanks. A long drawn out job but arguably easier than in 1971 where we had to row backwards and forwards with plastic jerrycans of water drawn from a nearby stream. In the left hand picture, you can just make out the ice axe and the saucepan used to scoop up the melt water and in the right hand shot, a rudimentary dam is just visible, complete with plastic piping and plastic cans slowly filling.

In addition to the food and water, we took on bonded stores including tobacco for the crew plus 2 Cases of White Horse Whisky, 2 Cases of Four Bells Rum and 2 Cases of Gordon’s gin. Drinks were brought out on Saturday evening, before the evening meal. Since the only mixer available was a large glass flagon of lime juice, spirits were mostly drunk neat – except for ice, which we had in abundant quantity. In higher latitudes, when the situation was favourable, we would take an ice axe to a convenient floe in order to provide a slight air of sophistication to the Saturday evening cocktail.

On one occasion at a peaceful fjord anchorage one Saturday evening, I rowed over for the ice with a bottle of Scotch. Framing a photograph with a glacier in the background, Sea Breeze in the middle distance, and a bottle of White Horse on a floe in the foreground, I had high hopes of making a fortune on the advertising market. White Horse, at the time, were running a series of advertisements on the theme of ‘You can take a White Horse anywhere’. On my return from the 1970 trip, a penniless student at the University of Wales, I sent the distiller a copy of the slide along with a suggestion for its use in their campaign. The response was singularly disappointing.