Tilman the baker and brewer

Much has been written of Tilman’s attitude to food, diet and expedition rations. Less well known, except to those who visited him at home in Barmouth, were his abilities as both a baker and brewer. Lunch at Bodowen – particularly welcome after a wet hitch-hike down from Bangor – centred around his home baked wholemeal bread and a quart bottle of a delightful, hoppy, home brewed beer.

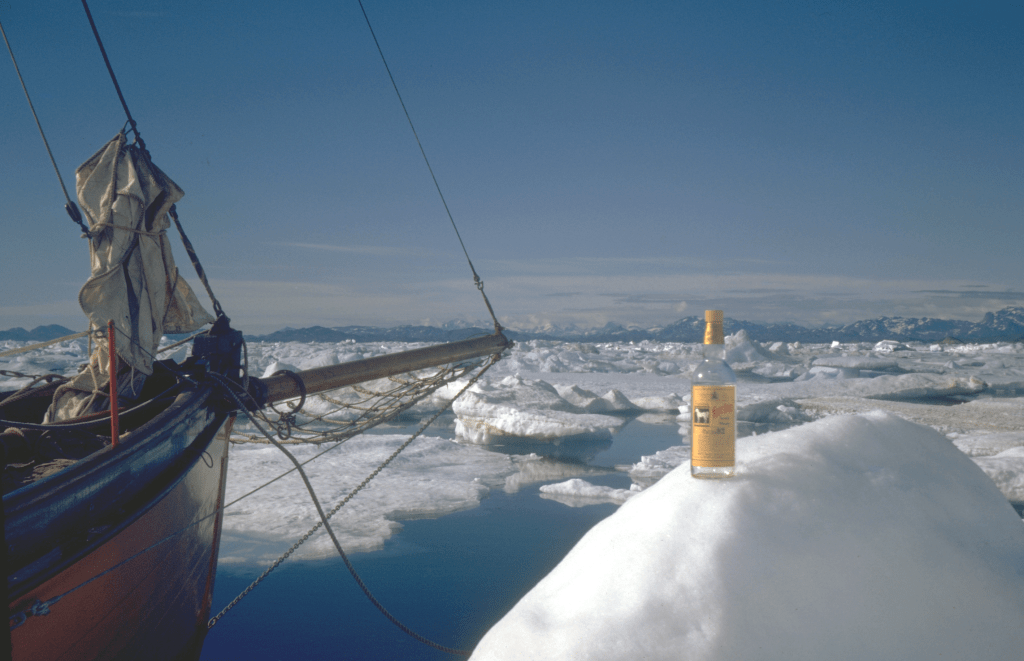

Lunch would be followed by a walk on the hills behind Bodowen, with black labrador Bella and Toff the terrier as company. The picture here shows Tilman with one of the sheepdogs at Egon Jensen’s farm near Nanortalik in 1970. We spent a few days anchored in a delightful inland fjord here, working on the boat and exploring the local scenery. The Jensen’s were running an experimental sheep farm in the south west of Greenland, an exercise which benefited from state funding from the Danish government.

Tilman’s attitude to his crews

Tilman’s attitude toward his crews varied in proportion to the extent to which they pulled their weight as part of the team. Both 1970 and 1971 proved to be good years for crew, but a number of the later voyages were not so fortunate. Where friction between crew and skipper became a problem, it was probably attributable to the crew containing a disproportionate quantity of ‘professional yachtsmen’ rather than ‘seamen’. The climbing members of the crews knew what to expect, trusted the skipper, and respected his judgment. The yachtsmen among the crew tended to question his actions and doubt his judgment.

Professional sailing experience wasn’t a skill accorded particularly high value by Tilman during his search for a good crew. What he looked for, usually with limited success, was the strength of character and attitude which would survive four months with four other men in an old 40 foot boat in cold, damp surroundings – hopefully working together as a viable team in the process. When a good team came together, it was largely as a result of efforts on the part of the crew themselves. Tilman himself did not go out of his way to foster team spirit in his crews and was not, in my view, a natural leader in the sense of being a commander. He was an individual who set himself very high standards of achievement and simply expected others to follow that lead as a matter of course. When they sometimes refused, he seems to have been taken by surprise. When they stepped up to the challenge, as they did to varying degrees on both of the trips that I made with him, then the team which resulted was close and effective.

The Biographies

I have been disappointed with each of the biographies. JRL Anderson’s writing in the Guardian, and particularly his “Vinland Voyage” was something of an inspiration to me when at school, so I already had some respect for him. The first year I sailed with HWT, he published a book called ‘The Ulysses Factor’ , a copy of which my parents gave me for Christmas that year. The book, which tried to link the character traits of a number of twentieth century explorers to some common factor, met with a stream of invective from Tilman, one of the subjects. The first official biography, also by Anderson, “High Mountains and Cold Seas” took that theme further and while it was a pretty well researched account, the style irritated me. (Strangely, after my father-in-law died some years ago, while sorting out his collection of tapes, I came across a cassette of a Radio 4 adaptation of the book – complete with ‘Ripping Yarns’ accents and sound effects. It was positively dreadful and the subject would have disowned it.)

The only television documentary to date, by John Mead who at that time worked with Harlech Television, made a promising start. John took the effort to track down a number of former friends and companions of Tilman, and came down to take a look through my colour transparencies. He took about 30 away to use for rostrum camera shots for his documentary, but none found their way into the finished program. The high point of the visit to the HTV studios for me was undoubtedly a conversation over lunch with Noel Odell – a perfect gentleman. The same session included Jim Lovegrove from the 1958 ‘Circumnavigation of Africa’, Ian Duckworth, the unfortunate scapegoat for the loss of Mischief, and Pam Davies, Tilman’s neice. The program suffered from being far too short – 53 minutes in which to attempt to cram in such a full life – a slightly better chance than Radio 4’s 30 minute farce – but nevertheless way too short.

I guess the difficulty with external interpretation of the original text is that the style is so deliciously dry and dismissive. On the outward voyage in ’70, there was a comment which ran something like “nothing much of note occurred, except for the night when Bob woke me up to look at a distant luminous object which I had no difficulty in pronouncing to be the rising moon”. In reality, we were closing Cape Farewell for the first time and he’d warned us to look out for ice, suspecting that there would be the odd berg coming down with the east Greenland current. He took the watch after mine and at the turn of the watch I remarked that I’d seen this strange luminous object on the starboard bow. It had long since disappeared (risen behind the low cloud on the horizon?), but he himself suggested it might have been the last rays of the sun catching on a berg. It was midday the following day, having spent an hour studying the chart and tables, that he suggested it ‘might have been the moon’.

In November 1998, the magazine Yachting World published an article by Tim Madge, effectively a precis of his 1995 biography, marking – somewhat belatedly – the centenary of Tilman’s birth – February 14th 1898. This article contained a comment about Mischief being “clapped out”, reawakening the kind of comments which are regularly made about Tilman and his boats. In a letter to the editor, Andrew Craig-Bennett, who like myself took exception to this reference, wrote the following comments:

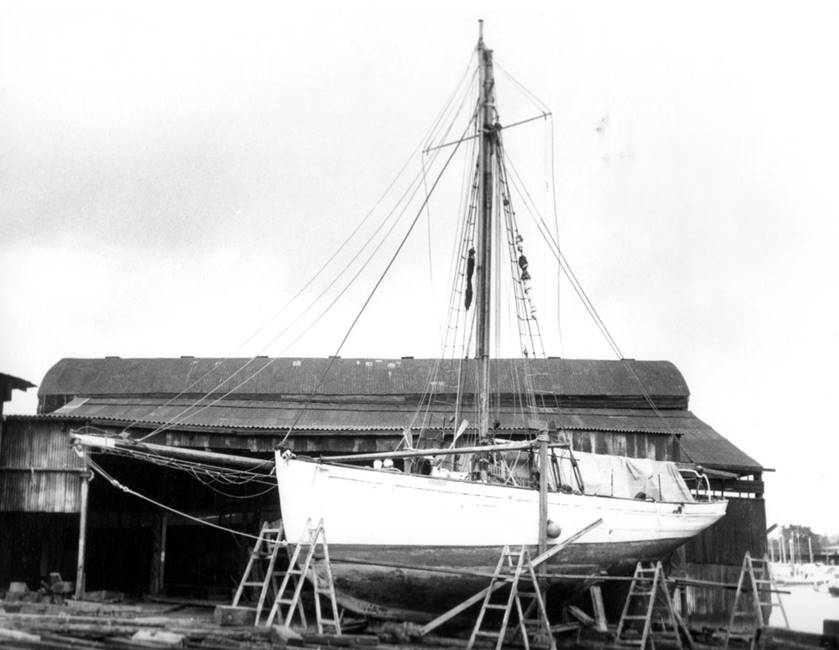

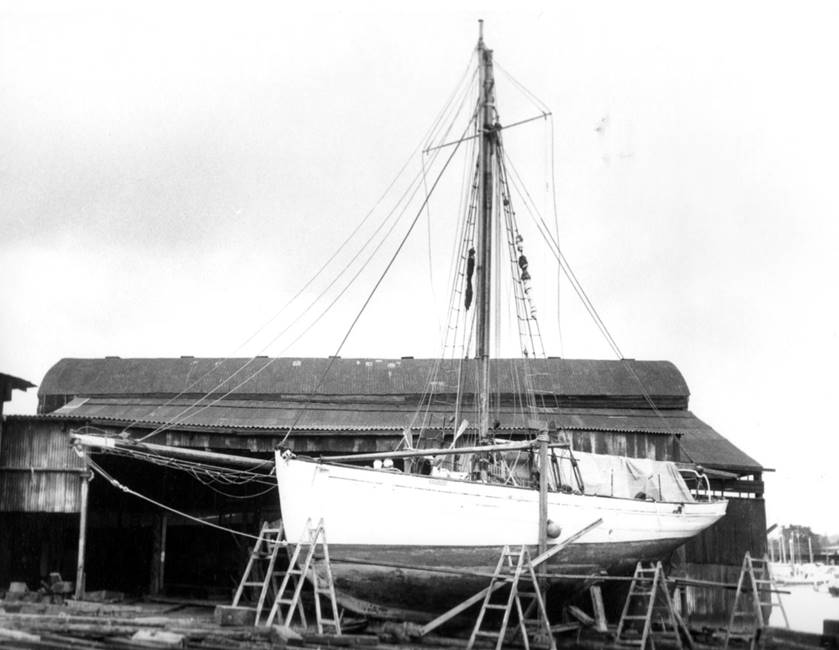

“Tilman was not so very inexperienced when he bought Mischief. He had learned his cruising and navigation from Robert Somerset, who had owned Jolie Brise and at that time owned Iolaire. He bought Mischief from Ernle Bradford, the writer best known for his account of the siege of Malta, on the recommendation of Humphrey Barton, to whom he had explained exactly the voyage he planned to undertake. She (and Sea Breeze) were surveyed for him by John Tew whose recommendations were carried out by the Berthon. In other words, he placed his requirements in the hands of the firm of Laurent Giles and Partners at the very height of their prestige. Mischief was not so very “clapped” and her owner was elected to the Royal Crusing Club pretty smartly!

Tilman wrote his sailing books in a style which is a deliberate pastiche of the “typical” voyage accounts of the day (engines “refusing to start”, etc!) and they are all the funnier for that. Unfortunately, Dr Madge takes it all seriously, invents drama where there was none and perforce repeats the myth of the crabbed, barely competent, misanthrope “out of touch with the times”, a persona which Tilman enjoyed creating but which was not the man who, at 76, would sit over his pint and pipe in a Lymington pub and tell amusing but unrepeatable stories!”

Bill Tilman had the good fortune, by birth, to have the private income to do as he wished. He had the equally poor fortune, by birth, to have been caught up in a war that devastated much of his peer community. His reaction was simply to make the best of a bad job, in which endeavour his sublime sense of humour clearly stood him in good stead. His own accounts of some of those wartime exploits, told over drinks on Saturday evenings in high latitudes – once the crew had earned his confidence – don’t always square with the interpretations of biographers who perhaps never worked with him.

I wouldn’t attempt to judge his achievements in Africa, the Himalayas, Yugoslavia & Albania, but as one who sailed over ten thousand miles with him on Sea Breeze, I believe I can speak with some authority on his later achievements as a sailor. Like Andrew Craig-Bennett, I am less than impressed by those who would pass him off as some kind of rank amateur in this field. That he did nothing to dispel this myth owes much to his natural modesty and mischievous sense of humour. In reality, as owner and master of a well maintained traditional working boat, he displayed levels of seamanship, ship husbandry and navigation which would put him head and shoulders above most of the readership of the popular yachting press. Apart from very rare occasions when tiredness may have clouded his judgment, his decisions were well timed, appropriate, and executed with all due care. The degree to which voyages could be classed successful was directly proportional to the level of trust and loyalty displayed by his crews. Those crews which gave him the benefit of any doubt, and put in the level of effort which he had a right to expect, were rewarded with some memorable experiences. Those which didn’t, were probably never pushed – resulting in some of the ‘comparatively humdrum’ voyages of later years. Sadly, Tim Madge’s biography seemed to have sought input from mainly the latter group.

A few personal observations

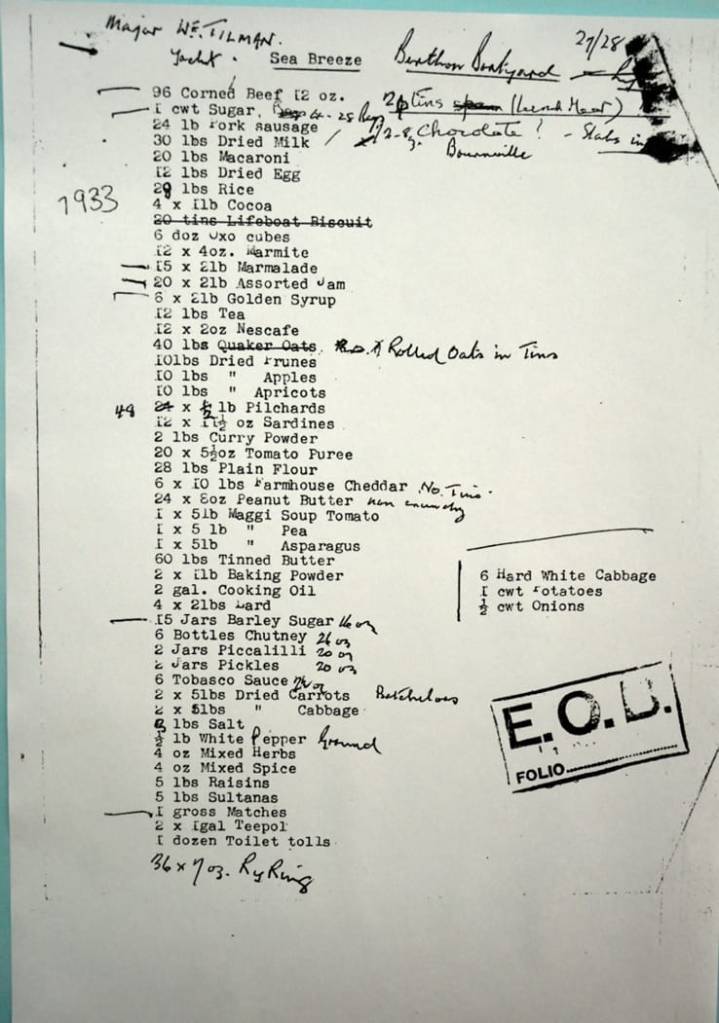

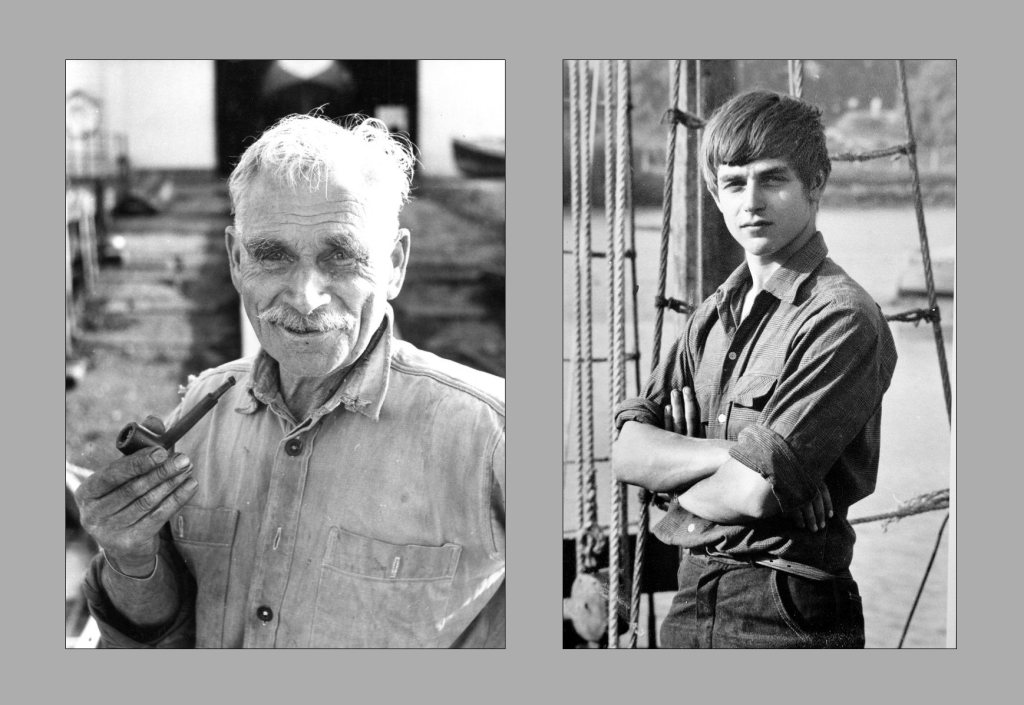

I first met Bill Tilman when I was 17 – “between school and university, slightly built – not likely to break a rope by heaving on it” – to quote his own first impression of me. At Christmas, 1969, I was at a loose end. I’d already qualified for a place at the University of Wales starting in September 1970 and a small crew notice in the Sail Training Association journal caught my eye. The skipper and vessel in need of a crew were one Major Bill Tilman and the Bristol Channel pilot cutter “Sea Breeze” which having been launched in 1899, proved to be a year younger than her owner. We exchanged letters, and in February I met him on the boat alongside the Berthon quay on the Lymington River. By the time we met, I’d already tracked down a couple of his books and thought I had formed a fairly accurate picture of both boat and owner – the latter illustrated by the old photograph which appeared on the back cover of each of his books. The boat held few surprises but I confess that I was somewhat taken aback by the appearance of the skipper – older at 70 and hardly a giant himself.

A quiet unassuming man – easy to overlook, even in a small group, until he chose his opportunity to raise the level of conversation with some perfectly timed and apt remark. His quick wit, often at his own expense, would be accompanied by a mischievous grin around the stem of an F & T pipe – of which he had a regular source of manufacturers rejects.

As a seaman, he was an old fashioned, unpretentious working-boat sailor – one whose preferred reference work was Captain Lecky’s “Wrinkles on Practical Navigation”. He viewed himself, and often portrayed himself, as an amateur, but anyone seeing him quietly going about the day to day maintenance which the old cutter required, would not help being impressed with the skills he’d picked up. The first few days out of Lymington, he spent many hours on either tack, hard at work with a marlin spike gradually setting up the deadeyes and lanyards at the foot of the shrouds. There were numerous other aspects of what was really historic ship maintenance in which he’d developed a high degree of competence, including repairs to the heavy flax canvas sails and the splicing of halyards and sheets. At the end of the trip, he’d take assorted blocks home for winter repairs – rarely trusting the boatyard with such items – and return the next season with newly made canvas buckets and other practical items.

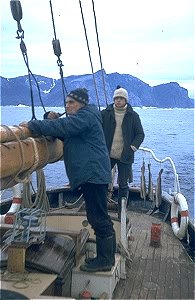

He was perfectly in tune with the boat, and never pushed her beyond reasonable limits in due consideration of her age. On night watches we sailed single handed, and with a freshening wind and too much sail on, the watch-keeper would normally need to call up assistance to take a reef in the heavy gaff main. Invariably, even in the midst of a deep sleep, Tilman would sense the need for action and would simply appear on deck unprompted.

There was a caring side to his character which is rarely documented, but to which I can testify. His genuine pleasure in my decision to sail with him for a second time was tempered with a genuine level of almost parental concern when I made a move to sign up for a third successive northern cruise. During the second trip, I’d received news that I’d failed a key university examination paper – taken in haste the day before making the almost pierhead jump onto the boat. Since I couldn’t return to England to retake the paper, I was effectively thrown out of college – something that he unfairly believed was his personal responsibility. I clearly remember sitting in the saloon, alongside the harbour wall in Reykjavik, shortly after hearing this news, with Tilman asking me whether it would help if he wrote to Charles Evans, his former climbing partner and at that time Principal of the University College of North Wales. At the time, neither of us thought it a proper course of action but it was, nevertheless, an indication of his level of concern at my predicament. (Interestingly, after we returned, I went cap in hand to see Sir Charles who, when he heard whose company I’d been in, made it abundantly clear that it was time I got my academic priorities in order!)

The voyages and conversations with Tilman left their mark, and have long since been a major influence on the way in which I treat working relationships. As a yardstick, the “how would this person fit on a high latitude small boat voyage for four months” test is a better test of a team member than any glowing inventory of skills – most of which can be acquired in time of need. Like Tilman, however, I sometimes still get that badly wrong!

He was clearly relieved when I started to settle down into a career in IT, although I suspect he’d have been horrified at the prospect of my still being there 35 years later! That nearly didn’t happen back in 1977, when he shipped with Simon Richardson on “En Avant” for the ill-fated voyage south. I came close to joining them on that voyage, but concerns about the boat got the better of me and I quietly withdrew and completed the settling down process by getting married instead.