Course

Lymington -Torshavn – Reykjavik – Isafjordhur – Angmagsalik – Sehesteds Fjord – Lymington

Crew

Bob Comlay – UK

Max Smart – New Zealand

Peter Marsh – UK (to Reykjavik)

Jim Collins – USA (from Reykjavik)

Marius Dakin (Cook) – UK

An east-about circumnavigation of the British Isles, via the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland. In Tilman’s view, humdrum in comparison with the previous year but nevertheless not without incident..

May 1971 saw the end of a my first year at Bangor University. While this had been a thoroughly enjoyable social experience, it was nevertheless an academic cul-de-sac from which I was only too glad to escape. The prospect of another two years in the company of some of the dullest members of humanity I’d ever come across – the School of Electronic Engineering – was too much to bear and escape to Greenland couldn’t come soon enough. I left the final examination paper early to catch a train home, to gather up kit in time to make a pierhead jump at Lymington the following morning.

Given my new found status as an impoverished student, I was alternating between Kodachrome transparencies and black and white film on this trip, so inevitably some of the more interesting events of this voyage were not covered by the slides. These include the time at Isafjordhur undergoing repairs to the prop shaft, the encounter with ice off Scoresby Sound and the voyage home. Most of the colour shots I have of our time in Iceland relate to a trek over to Gulfoss, one of the many beautiful waterfalls in that country, across the dry volcanic landscape.

I arrived on the run from Bangor having skipped half way through my last examination paper in order to get to the train, to find the ship & crew ready to let go the moorings and set sail. We sailed westward, past Hurst Castle and through the Needles Channel, before the skipper decided to go eastward, through Dover and into the North Sea. In falling winds, progress was slow and we crawled up the English Channel – spending a day drifting backward and forwards past the Royal Sovereign light. Traffic in the Dover Straights was frighteningly busy – given our lack of manouverability and the larger vessels lack of regard for an aging pilot cutter. It was with some relief that we passed through the sraights and headed north of the Goodwins, away from the bulk of the traffic, and into the North Sea.

As night fell, we soon found ourselves in the centre of what seemed almost like a large floating city – oil platforms as far as the eye could see, covering and area which on Tilman’s ageing North Sea charts should have been nothikng but open water. Peter, all the while, had been constantly seasick – doing his best to stand his watches – but clearly in a great deal of discomfort. A PT instructor by trade, he had invested many hours in designing and building a catermaran with the sole intention of sailing North to Jan Mayen to climb. Having built the boat, he’d undertaken several short distance trips – each one marred by what he believed to be short term seasickness. As we sailed on Northwards, it became steadily apparant that Peter was cursed with the far less usual chronic form of sea-sickness, for which no easy remedy exists, short of heading back to dry land.. Max also was far from well – being far more used to trekking into the hills overland rather than over water. Still, the attraction of Greenland was enough to quickly aclimatise him.

Our original first port of call was to have been Reykyavik, where we would wait for favourable ice reports before making a stab at Scoresby Sound. After wrestling against wind and tide through the Pentland Firth – supplementing ‘all plain sail’ with the dreaded Kermouth Hercules diesel, we found ourselves with a westerly wind morer suited to a northerly course.

With Sea Breeze finally flying along past the haystack shaped Islet of Litla Dimun in a freshening westerly, with poor visibility and no current chart of the approaches to Torshavn, we headed into Sando and dropped anchor off the tiny hamlet of Sandur.

Rowing ashore to take a look around the village, with its characteristic grass roofed church, we soon fell in with a local family who pressed hot drinks and gifts of Faroese wool mittens & socks on us. There were sheep in evidence everywhere, grazing in the fields and on the turfed roofs of various outbuildings. Strange then, that we learned later that one of the principal imports to the islands was sheeps heads from Aberdeen. The following day, we headed up to Torshavn in bright sunlight.

The picture above was taken on the approach to the harbour, the Skipper slightly confused by the appearance of a large breakwater since an earlier visit some years before in Mischief. The appearance of a bright yellow Pilot Cutter in the harbour entrance flying the Red Ensign didn’t go unnoticed by the authorities, and as Tilman set off in the dinghy to report to the harbourmaster, he was soon picked up and towed sheepishly back to the cutter astern of the harbourmaster’s launch. The harbourmaster himself was more concerned with ensuring that our supplies of spirits were properly locked away before any of us left the ship unattended.

Alcohol was strictly limited to personal use only in the islands, which were effectively ‘dry’ as a result. The bars and cafes around the town were there purely to supply tea, coffee and non-alcoholic beverages only. Having said that, Torshavn remains one of the few towns I’ve ever visited where the adult population. almost without exception, seemed delightfully and peacefully inebriated as soon as night fell. Under the counter sales of whiskey and beer seemed to go on in the shadows everywhere, thanks to ‘imports’ from Aberdeen trawlers.

The islands themselves – like Greenland – were in the early throws of attempts to gain independence from Denmark. Uncorrupted by television, the islanders had recently launched a Faroese language newspaper and were trying to get Faroese adopted as the first language in the schools. All this peace, beauty and simplicity of life left strong impressions which are still clear in my mind today. It complemented the fact that we were also on a boat which had been built in 1899, and which had no radio, and no technology save for a very old, very smelly, very noisy and only very occasionally used, engine. So – for four months in 1970, and four months in 1971, I was completely out of touch with so-called civilisation – an experience I’d recommend to anyone. In 1970, we had not stopped until we reached the west coast of Greenland, but in 1971, we stopped at two very different islands on the way – Faroes and Iceland – both locked in unique northern lifestyles.

Tilman kept himself to himself and stayed on board most of the time we were there, which the rest of us spent a few happy days wandering around the town and enjoying the happy relaxed atmosphere. Everywhere we went, we were greeted almost as long lost friends, and the hospitality that we enjoyed made us all reluctant to leave by the time we had to. In truth, we were all blown away by the natural beauty of the local ladies, which along with the peaceful beauty of the islands themselves, became the prime topic of conversation for some days afterwards much to Tilman’s very evident confusion!

Tilman decided to call in at Torshavn, partly to give Peter an opportunity to call it a day, and partly out of curiosity since it had been some years since a previous visit. As it was, Peter insisted on carrying on to Iceland in the belief that the sea-sickness would improve. It never did, and he spent a miserable week en route to Reykjavik living on a diet of salted peanuts, of which he had a plentiful supply – the only food experience had told him that he could keep down. Unfortunately, this peculiar diet also required more frequent trips to the galley for drinks of fresh water than our daily ration would permit – leading at times to some tension with the cook, who’s role included the policing of fresh water supplies. Unlike her predecessor, Sea Breeze had rather small and inadequate fresh water tanks, which had led us to go to some extraordinary lengths the previous year to keep them replenished from meltwater on icefloes.

While we were in Torshavn, we were on a mooring next to Westward Ho, a beautifully maintained Grimsby trawler a few years older than Sea Breeze. These two old working sailing boats, together in this small northern harbour, made a delightful site. Westward Ho was preserved as a kind of national property, as reflected in this stamp, but I’m not clear on the exact history of the vessel and how she came to be there – so far away from home.

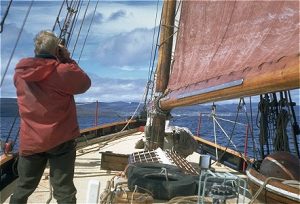

On watch somewhere in the Denmark Straight, in light airs. Note kicking strap in place on the boom to safeguard against sudden movement of this one ton spar due to the rolling of the boat. Given that I’m seen here standing on the cockpit lockers, deep in conversation with another crew member, this was probably a good idea! The unusual stance can actually be explained by the need to see ahead of the boat when sailing in loose ice. The hydraulic winch in the foreground, together with the dinghy stowed on deck, restricted visibility considerably.

Leaving the islands, we sailed for Reykjavik, spending three weeks working on the boat and indulging in a little tourism while the Skipper took a daily trip out o the airport to get first hand updates on the ice conditions off Scoresby Sound. Tilman had already made several attempts to get a boat into Scoresby Sound, at the head of which were to be found two mountainous islands with many peaks which, in 1971, had yet to be climbed. This passage from ‘Ice with Everything’ sets the scene:

“Wide though the choice of objectives in northern waters may be, I had no doubts about where we ought to make for in 1971. No one likes being defeated and our tame acceptance of defeat when trying to reach Scoresby Sound in 1969 still rankled. On that occasion, when some 20 miles south of C. Brewster, the southern entrance to the Sound, what I called a polite mutiny on the part of the crew had obliged us to give up and return prematurely home. Admittedly, our five days of groping in continuous fog had not been encouraging and when the fog had cleared sufficiently to reveal a lot of ice—a phenomenon not unexpected in the Arctic—the crew decided they had seen enough. Ice reports that I obtained after our return showed that we might have had trouble in entering the Sound and certainly more when leaving it, but this is what the voyager likes to discover for himself and this is what a voyage of this kind is all about.

Scoresby Sound is in Lat. 70° N. on the east coast of Greenland. The Sound was named after his father by William Scoresby, who in 1882 surveyed and charted some 400 miles of the east coast. Like his father, he was one of the most successful whaling captains sailing out of Whitby and, not content with this, he went on to become an explorer, a scientist, a Fellow of the Royal Society, and at last a parson. Having made his first voyage with his father at the age of eleven, after twentyfive years at sea he went to Cambridge to take a degree and entered the Church. His two-volume book An Account of the Arctic Regions, with a history and description of the northern whale-fishery, should be read if only for the story of how they saved the whaler Elsie, nipped and badly holed a hundred miles inside the pack.

The real objective is two little known, highly mountainous islands on which no climbing, I believe has yet been done, and these lie some 70 miles inside the entrance. Seventy miles is no small distance and since the Sound would be by no means entirely ice-free it would probably have to be done under the engine. There are therefore difficulties and hazards enough in the way of winning this particular prize. Scoresby Sound, by the way, is the largest fjord in the world. Some merit would be acquired by getting there in a small boat and at the back of it are these two islands studded with unclimbed peaks.”

(to be continued – 12/11/2016)